One thing about growing up with strong matriarchal ties: you develop a practice of doing what you are told. My earliest memories are of large, God-fearing aunties scolding me not to touch the knick knacks, the books, or much of anything when I came to visit. I remember sitting on plastic-covered couches with my knees pressed dutifully together, stiff and upright as a rod, and feeling that vinyl melt into the back of my legs; I can feel the sting and hear the scrisssh sound of my skin peeling away when I got up to go home.

If I can remember that sensation and sound, this means I would have been wearing shorts, and if I remember the 70s right, that would have be on point, fashion-wise, but already a stylistic affront to the full skirts and Southern gentility with which they’d been raised and which they expected of all generations, less we be ‘loose.’ I definitely came up from the side of saints, not sinners.

That said, life since the vinyl-covered couches has been a lot more freewheeling. For me, in order to make my place in the world, I have had to be bold; as a First-Gen collegian, a girl from East Harlem inserted into New York’s toniest girls school at age 12, and through all the phases of life that have followed. It’s been a journey of knowing when to be quiet and when to speak out and push forward. I haven’t always made the perfect call, but I’ve certainly learned a lot.

Along the way, there have been many women who have wanted to offer schooling: from my mother trying to teach me how to make the soul food of our Brave Sis ancestors, to my older sister recently showing me how the super-modern makeup hack of how to “bake” my eyebrows. I lived with a wonderful family of considerable means during the last years of high school, and the mother, seeing the willing audience her own children were less amenable to provide, was always sharing her advice with me on how to live my future life. Memorably, she told me I needed to have lots of children since I was so smart, and the world needed more intelligent Black people to be in leadership roles. These nuggets of wisdom were based on her coming of age in the 1950s debutante New York, but some of them made sense, and they definitely helped me learn to navigate une certaine demi-monde, which has proven useful.

My high school teachers were beloved and trusted advice-givers, and in many ways, were among the last older women whose insights I heeded with no equivocation. Wellllll, wait: when I lived in Paris, there were a few older women I learned from. Observing them showed me how to grow older with style and grace and a bit of fearlessness. This felt like a cultural master class, adulting à la française.

In the workplace, lamentably, I have never had an official career mentor or been part of a professional support group of any kind, so a lot of that learning has been force-fed with the backdrop of “do what I say because I pay you.” Sometimes with me grumbling under my breath that their tutelage was inspiring me to actually do the opposite! It's interesting to observe how the younger generations in the workplace are pushing back against even these strictures…

My other career, that of mother, has been more circular in its economy, supported by advice from other co-mothers and girlfriends in my cohort teaching me all sorts of helpful things about childcare, education, family health, the good camps, all of that.

In the social circle, though, it’s been messier. Not with my group of trusted girlfriends, but another one, two or three rungs out.

Maybe it has to do with tone of delivery: “you really should…” “in my opinion…” “why don’t you…” and sometimes flat out: “do.” Like at the auntie’s homes, I have tended to sit on the couch quietly, not necessarily saying “yes, thank you” to the advice, but finding a way to pull myself off the couch without too much scrisssh.

Interestingly though, as much of this opining has been doled out under a lens of a so-called, “shared feminism,” I’ve started feeling less willing to let so many others douse me with unsolicited advice. Reading and learning from Robin D’Angelo and her groundbreaking work White Fragility has also lifted up an uncomfortable truth: there is a certain type of liberal white woman of a certain age who tends to lean in a little too hard with the advice, dipping precariously into the “pushing-around” category. And as D'Angelo writes, they don't even see it. It's a goal of Brave Sis to help us all see that which is harder to glean.

Digging into history a bit, as I have done, is revealing some very interesting inflection points in our American story of women, among them that one of the great stories of "sisterhood," the suffragist movement, was veneered with a slimy slathering of anti-Black women racism. Called out by Ida B. Wells and others, it played out somewhat along the lines of “white women in the South are our closer kin than these formerly enslaved women.”

Having written about so many Black suffragists in researching the Journey-Journal, I’m wondering what their actual interactions with the Susan B. Anthonys and the Elizabeth Cady Stantons really might have been like. In realizing the extent to which these women were not really “allies” (a word I'm finding increasingly troublesome; like "tolerance," it implies a have and a have-not) to their Black sisters in the movement, and in thinking about other moments in our history, one does start to question the motivation, or at least the optics, of so much unsolicited forced advice.

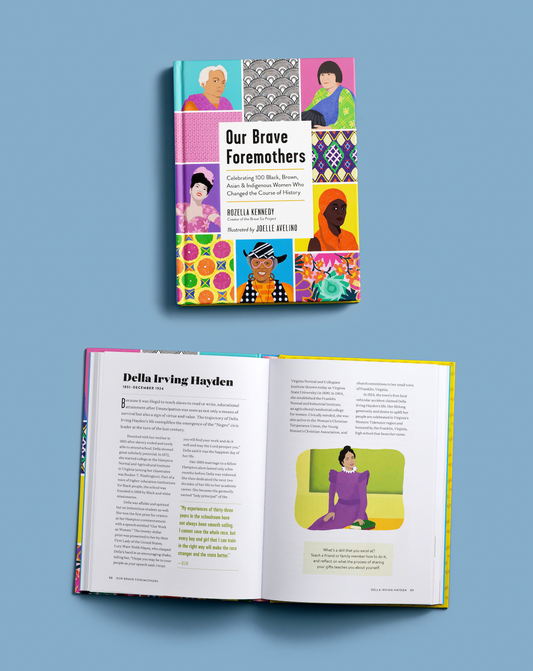

In the course of putting this Project together, I have had more than half a dozen women (I'm sorry to say, all white, some of whom I barely know) tell me what they think the Project should be—particularly at the vulnerable moments at the beginning of the work. Frankly, if I had listened to them, there wouldn’t even be a Brave Sis website, much less a logo, an LLC, a prototype, or a business plan. But because it's the foremothers who are guiding me, I felt I could hide a little in their apron strings and keep doing what they are telling me to do.

I’m reminded of other times when I did not have enough personal strength and wisdom to tell these ladies “thanks for caring, but I’m not taking your advice.”

I, through Brave Sis, want to help others find the way to say this, no matter what your age!

In embarking upon and sharing out this work, I’m gaining a new understanding about why so many women in their 40s-60s have solicited me for help ‘navigating’ complicated workplace relationships with Women of Color in younger age brackets. One piece of advice I would like to give is, “white woman, dear friend, take yourself out of the center of the narrative.”

Doing so requires an actual reworking of how we look at society, media literacy, and “norms.” It is hard work, but doing it is part of what I think can help white women be in more authentic relationships with Women of Color. I’m doing an enormous amount of study on this topic right now, both through the Project, and through historical and contemporary readings.

Here’s a personal story. There was a woman in Santa Fe (I think you'd call her a frenemy; ever cheerful, over-solicitous, edgy, waaaaay opinionated) who asked me, at a fancy dinner if I were pregnant (I remember, as a mom of little kids who made a Herculean effort to spruce up, feeling so deeply deflated by that comment. I thought the Empire-waist dress made me look slim, not like Lucille Ball hiding her baby bulge from the camera). My reply: “no, that would be rather unwelcome news at age 48.” Hers: “well you really should work your core muscles, in that case.” This was from a pear-shaped, 60-something woman, which would have made me chuckle if I hadn’t been so hurt.

I responded with the only words I could muster through my frustration: “I guess I just have a Black girl body and sorry if my sway back makes you think I’m pregnant at age 45.” She was somewhat aghast, though I’m not sure if it was by what she’d said as much as how I’d responded. Or the fact that I introduced an uncomfortable racial truth into the conversation. Because a lot of Black bodies do look like mine, and this was several years ago, when “beauty” norms were still more constrained—curves are in now, child!

In the moment, I felt kinda mean making her feel bad, but I realize now that the Brave Sisses would have advised me “girl, please.” There’s another longer, history-based discussion about who wields out the harm and who does the consoling, but that's more than I should get into in this short essay.

For the record, I have asked other Women of Color about their experience with this kind of frenemy dialectic, and this experience is widespread to almost the point of universality. Breaking the silence around this issue is one of the broader outcomes I hope the Brave Sis Project can foster.

The whole point of becoming an adult (at any age), of gaining and honoring one’s voice is to learn to think for oneself, and to trust one’s own inner guide-star well enough to navigate to where you have to go. I just finished writing the Brave Sis entry on Harriet Tubman, and here are the final words of the Brave Sis Journey-Journal: Tubman worked in winter, when the nights were longer, guided by the North Star. As you consider her courage and heroism, what is your North Star: what personally guides you through your own darkness towards the light and a deeper freedom?

As we build out the Brave Sis community, one of the things I hope to seed is a place where we share ideas, inspiration, and hope, but most of all, where we learn to listen. To listen to the foremothers. To listen to lessons and offerings (when solicited). For white women to listen to Women of Color instead of barrel in with the game plan. But most of all, and beyond it all, to listen to ourselves. Listen, trust, learn. Be your own North Star.

And take that old-fashioned vinyl off the couch too, while you’re at it.